With former Oz authors (or, to use the more proper term, Royal Historians) unwilling (Ruth Plumly Thompson) or apparently unable (Jack Snow) to write more Oz books, publishers Reilly and Lee decided to take a major chance with their next book, picking a manuscript by an unknown, unpublished author that had come in through the slush pile.

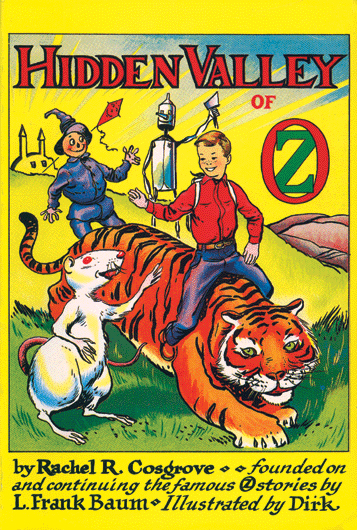

The author, Rachel Cosgrove, lacked both Thompson’s professional experience and Jack Snow’s long standing immersion in (some might say obsession with) Oz. But she did have a genuine love for the series. Perhaps more importantly, from Reilly and Lee’s point of view, as an excited first time author, she was more than willing to make all of the many changes requested to her manuscript, The Hidden Valley of Oz. Once made, Reilly and Lee, aware that long gaps between books were not helping declining sales, moved quickly to put the book into stores just in time for Christmas 1951. Judging by the hideous illustrations, perhaps a bit too quickly.

It’s easy to see why Reilly and Lee thought the manuscript might work: The Hidden Valley of Oz is essentially a milder version of L. Frank Baum’s The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. Here a young American child (in this version given the irritating name of Jam) travels to Oz; when he arrives, he’s assumed to be a magician; he’s then asked to destroy an evil tyrant before he can go home. Hidden Valley even features the same characters: Dorothy, the Scarecrow, the Tin Woodman and the Cowardly Lion all tag along, joined, somewhat inexplicably, by the Hungry Tiger and a rat named Percy. (I can only assume that the Hungry Tiger tags along so that both Dorothy and Jam have the opportunity to ride giant cats, but, otherwise, the Hungry Tiger doesn’t need to be here.) The book also parallels or outright borrows incidents from other Baum books, giving the book a distinctly repetitive feel.

(Hidden Valley makes no mention of other Oz books besides Baum’s. The still alive and irritated Ruth Plumly Thompson had requested that her characters not be used or mentioned. Cosgrove apparently had not read or heard of Jack Snow’s books before writing her own, and if she chose to ignore the confusion of John R Neill’s contributions, she can hardly be blamed for this choice.)

It’s not that Cosgrove doesn’t add her own elements—she does, with a visit to a land of talking kites, an encounter with living books, and a trip to Icetown, even though all of these, too, are reminiscent of earlier trips to the little side kingdoms and odd places of Oz. Particularly the encounter with the living books, where Cosgrove indulges her own love for wordplay and has distinct fun with allowing the books to hold a criminal trial. As it turns out, one of their murder books has cruelly murdered the English language (in the form of a nice scholarly textbook); you will not be surprised that their idea of trials lacks something.

But even this fun moment echoes a similar incident from The Emerald City of Oz. (I’m also a little uncomfortable with portraying books as openly hostile, but that might be just me.) Other original bits just don’t make much sense. To escape a frozen igloo, for instance, the characters decide to burn the Scarecrow’s straw, which begs two questions: just how much straw was he stuffed with, and, why aren’t they using the Tin Woodman’s handy dandy tin axe, which a few pages later is proven to be powerful enough to destroy magical trees and hypnotize multiheaded beasts? Surely that could have knocked over the igloo in seconds, without having to burn anyone’s straw? And Cosgrove also has no idea how to handle large groups of characters. Perhaps in recognition of this, a couple of characters (a leopard that does change his spots and a living rhyming dictionary) who join the party without any real reason later leave the party without any real reason just chapters later.

The chief issue with the text, however, lies with the language. It is often flat and, more problematically, filled with repetitive phrases and terms that often feel off and sometimes even intrusive: Percy the Rat’s constant use of “kiddo,” “kiddo,” “kiddo,” gets especially grating. To be fair, the language issue may have been yet another poor editorial intervention: Cosgrove later complained that she’d been asked to add various phrases and exclamations, including “golly,” that she’d never heard any real child say. And, for the first time in an Oz book the poetry, apparently rewritten by an advertising executive in an effort to prove that working in advertising might not be the best place to learn about poetry, is downright awful.

Also downright awful: the illustrations. For the first time, I found myself looking at them and thinking, hey, I could do better than that. Here are the various things that Dirk Gringhuis, who was understandably not invited back to illustrate any more Oz books, cannot draw, or, at least couldn’t in this book:

- Rats

- Tigers

- Children

- Children riding tigers

- The Tin Woodman (Ow. Just. Ow.)

- Perspective

- Trees

- Animal feet

You get the idea. The entire book has perhaps one or two sorta competent illustrations (of the kites, and later of some snowmen, and I guess the picture of the igloo could be worse) and even those feature the same heavy, thick lines that mar the rest of the illustrations (although I guess not being able to see some of the illustrations clearly is actually a help.) I can only assume that Reilly and Lee decided that speed was more important than quality here. And I’m assuming speed was the problem, since Dirk Gringhuis, who wisely refused to sign his entire name to this book, did recover from this to go on to illustrate other things, and did have professional art training—not that it shows here.

With all this said, if you can get past the illustrations, Hidden Valley of Oz is still an enjoyable light read, if not among the best of the series. I liked Spots, the leopard of the changing colors, and I adored the idea of talking kites, especially talking kites set free to roam the world and go visit other kites. And in another nice touch, Cosgrove shows her characters actually thinking their way through problems. If I am slightly skeptical that a swirling axe can be used to send a three headed monster into a benign mesmerized state, switching his (Their? I never know the correct grammar for three headed monsters.) personality from hostile to peaceful, I’m at least pleased to see characters coming up, and then following through with, a rather clever plan for defeating the monster and his giant master.

Also: the triumphant return of Ozma fail! Not that we were missing it or anything. Alas, after a too brief moment of competence, Ozma has retreated right back to her neglectful self, letting giants terrorize her kingdom, taking off for extended vacations, and leaving no way for her subjects to reach her in times of emergencies. This is one Ruler in desperate need of a cell phone. (Never mind that they hadn’t been invented yet. Oz has all sorts of things that haven’t been invented yet. Embrace technology, Ozma! You, of all people, sorely need it.)

Sales of Hidden Valley were disappointing, and although Cosgrove continued to write Oz stories, Reilly and Lee turned down her manuscripts. (Her second Oz novel, The Wicked Witch of Oz, was eventually published by the International Wizard of Oz club in 1993.) Her demand that she be paid the same royalty rates as Thompson and Snow, instead of receiving a lump sum payment for her manuscript, may have impacted their decision. Undeterred, Cosgrove moved on to a busy career penning science fiction and mystery tales. (Rumor has it that at SFWA [Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America] meetings, she grew frustrated when fellow writers wanted to chat with her about Oz.)

I have mixed feelings about this. For a first novel by a young and otherwise unpublished author with no other writing experience, Hidden Valley shows considerable promise, and I would have liked to have seen what she might have done with her love of Oz. On the other hand, had Rachel Cosgrove been named the official and continuing Royal Historian of Oz, Reilly and Lee would never have approached—or been approached by—the mother/daughter writing team of Eloise Jarvis McGraw and Lauren McGraw, who created one of my all time favorite Oz books—indeed, one of my all time favorite childhood books, period—in Merry-Go-Round in Oz, coming up in the next post.

One more note: Thanks, everyone, for your kind words on the How’s Our Driving and the Two Years of Tor.com Highlights posts!

Mari Ness had to draw her own little pictures of the Tin Woodman to soothe her feelings after reading this book. She lives in central Florida, where she tries not to inflict her artwork on anybody.